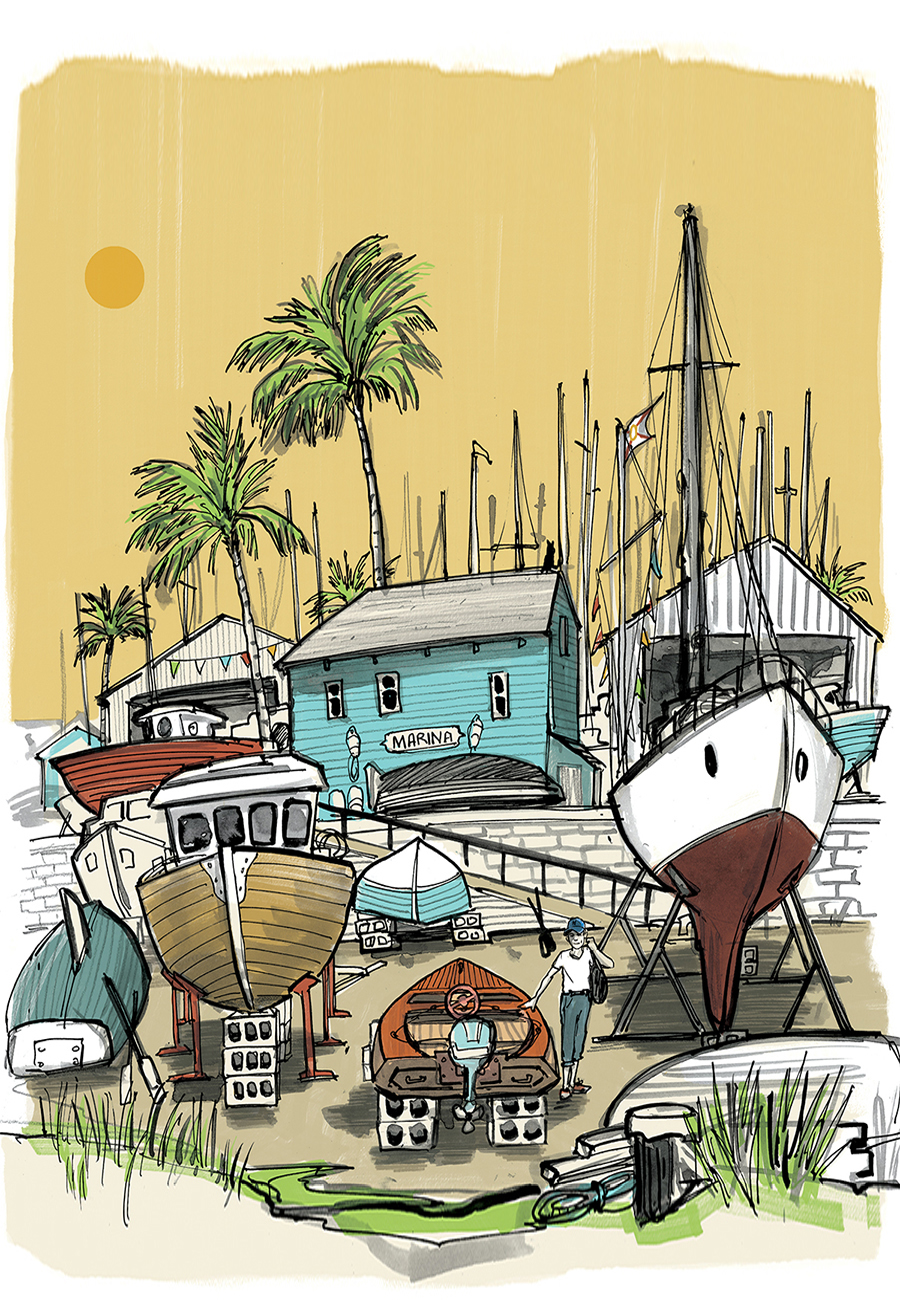

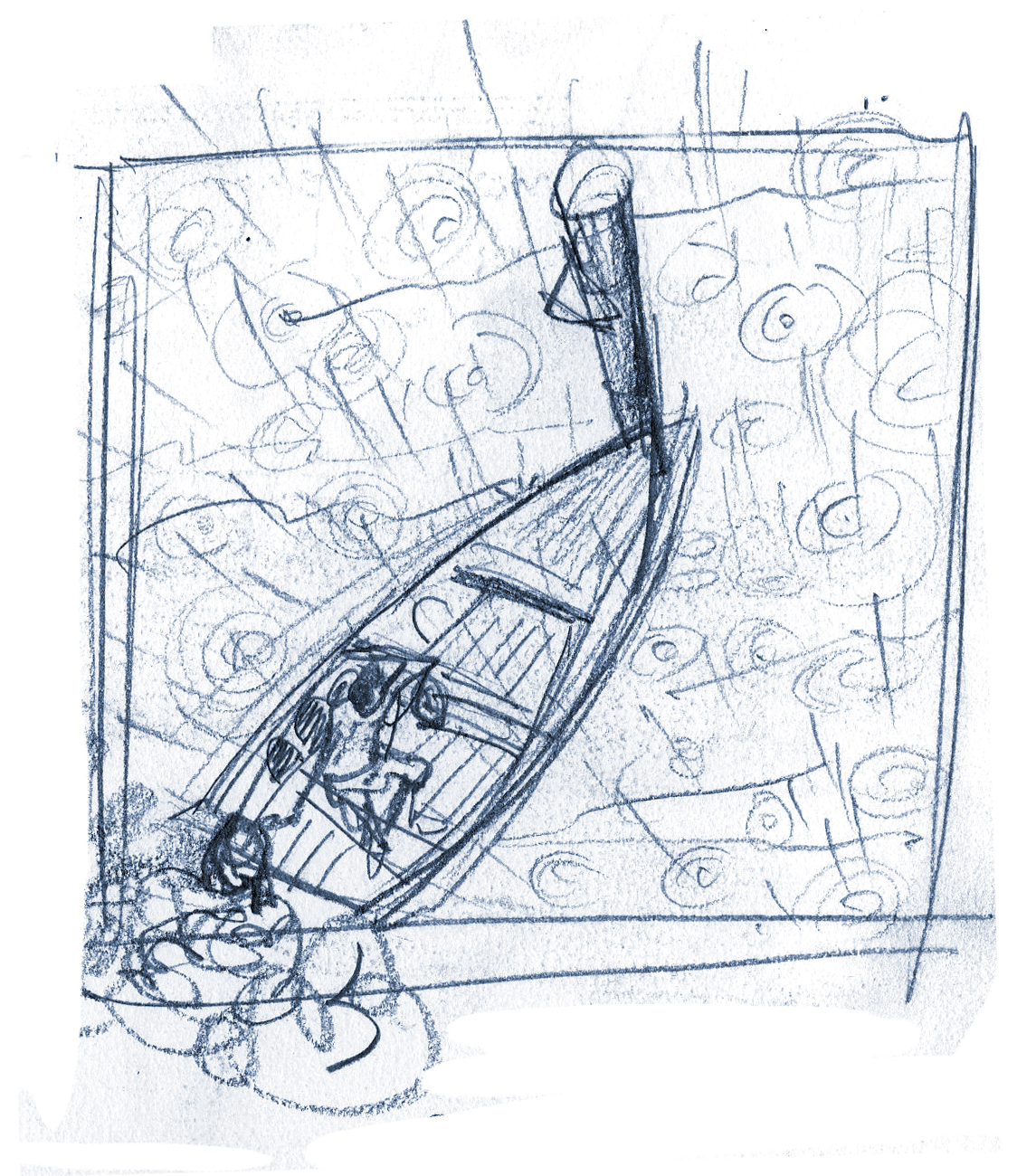

In the summer of 1957, at 16 years old, I worked at a small marina on Long Island, New York. I was able to save some money and buy a used 13-foot wooden Speedliner with a 1951 25-hp Evinrude. It was a fun boat, and my friends and I got many hours of use out of it, for waterskiing, day trips and spending time at the beach.

My mom did her best to support me and my siblings but it was a challenge. She sent me to live with family and go to high school in Miami, Florida. She didn’t own a car, so I had to figure out how to get my boat down there. I decided to run her south. My mother was against the idea at first, but eventually she gave in, although reluctantly. I’m certain she had no idea of the magnitude of the trip. Honestly, neither did I.

I bought every chart necessary (there was no Loran or GPS in those days), and used all my spare time getting things ready. The girl I was going out with at the time was the daughter of a successful charter boat captain. I was planning to leave on a Thursday in early August and I made my intentions known. A few days later, my girlfriend said that her dad was going to stop me from going, since “it was a dumb thing to do.” To make sure no one interrupted my plans, I moved the departure date up a day without telling anyone. When I was ready to go, I walked many miles to the dock in the middle of the night. I had loaded up all my worldly belongings (a single bag) into the boat the night before. I quietly untied the boat and paddled a fair distance up the canal away from my girlfriend’s house so as not to wake anyone. When I was sure no one would hear me, I started the motor and was on my way.

I can still remember that first morning: The seas were flat but incredibly foggy. I picked my way slowly from marker to marker until I reached Jones Inlet and the Atlantic. As I ran along the south shore of Long Island, I was careful not to get inside the breaking waves, since my boat would have made a very poor surfboard. I could tell by ear when I drifted too close to the breaking waves; I’d turn left to keep from being washed up on the beach. I was able to follow my progress by locating each inlet marker I passed on my charts. Eventually I decided to head a little more south into the open ocean to reach New Jersey through the Manasquan Inlet.

As I crept along in the fog, it suddenly got very dark. As my eyes were adjusting to the growing darkness, I thought I saw an object in the fog ahead of me. At the last second I grabbed the wheel and made a hard left, running along its side; I had come within a few feet of running into a large freighter headed through the Ambrose Channel to New York Harbor. I remember the much larger vessel’s prop roaring and realizing they could have run me down and never even known I was there. My teenage mind saw this as a great start to the trip.

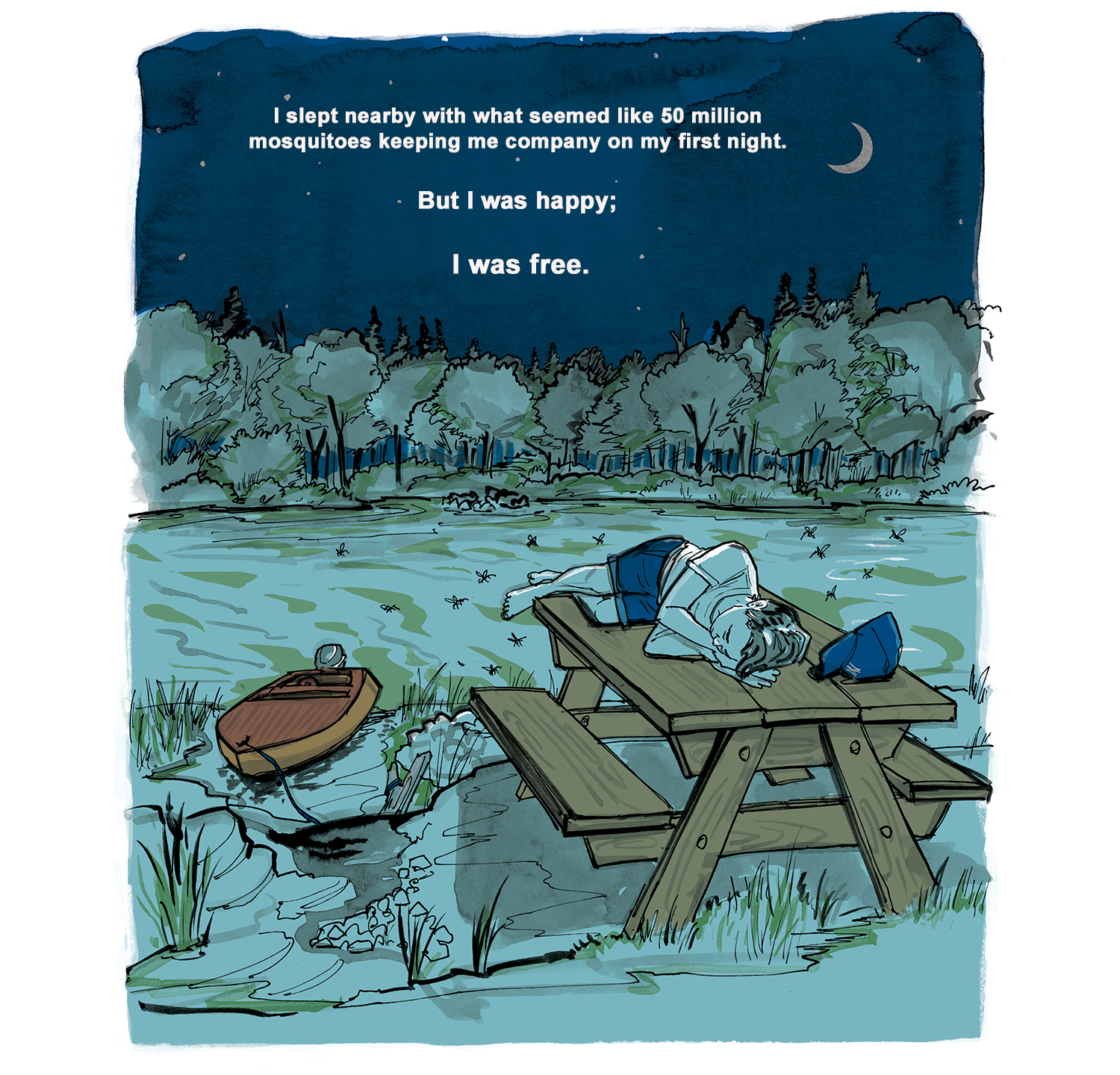

During all that maneuvering around the freighter, I noticed my little fisherman’s compass spinning wildly at each turn. To get a solid heading, I had to forcibly detach the compass from the dash and hold it in my hand. It dawned on me then that the steering wheel was metal, and affected the compass drastically. Had I not realized this at this time, I probably would have missed the entire state of New Jersey! So with compass in hand, I finally left the ocean through a nasty Manasquan Inlet just as the fog burned off. After running down through the winding inland route, I pulled my boat up on the beach at the east end of Cape May Canal. I slept nearby, on the ground, with what seemed like 50 million mosquitoes keeping me company on my first night. But I was happy; I was free.

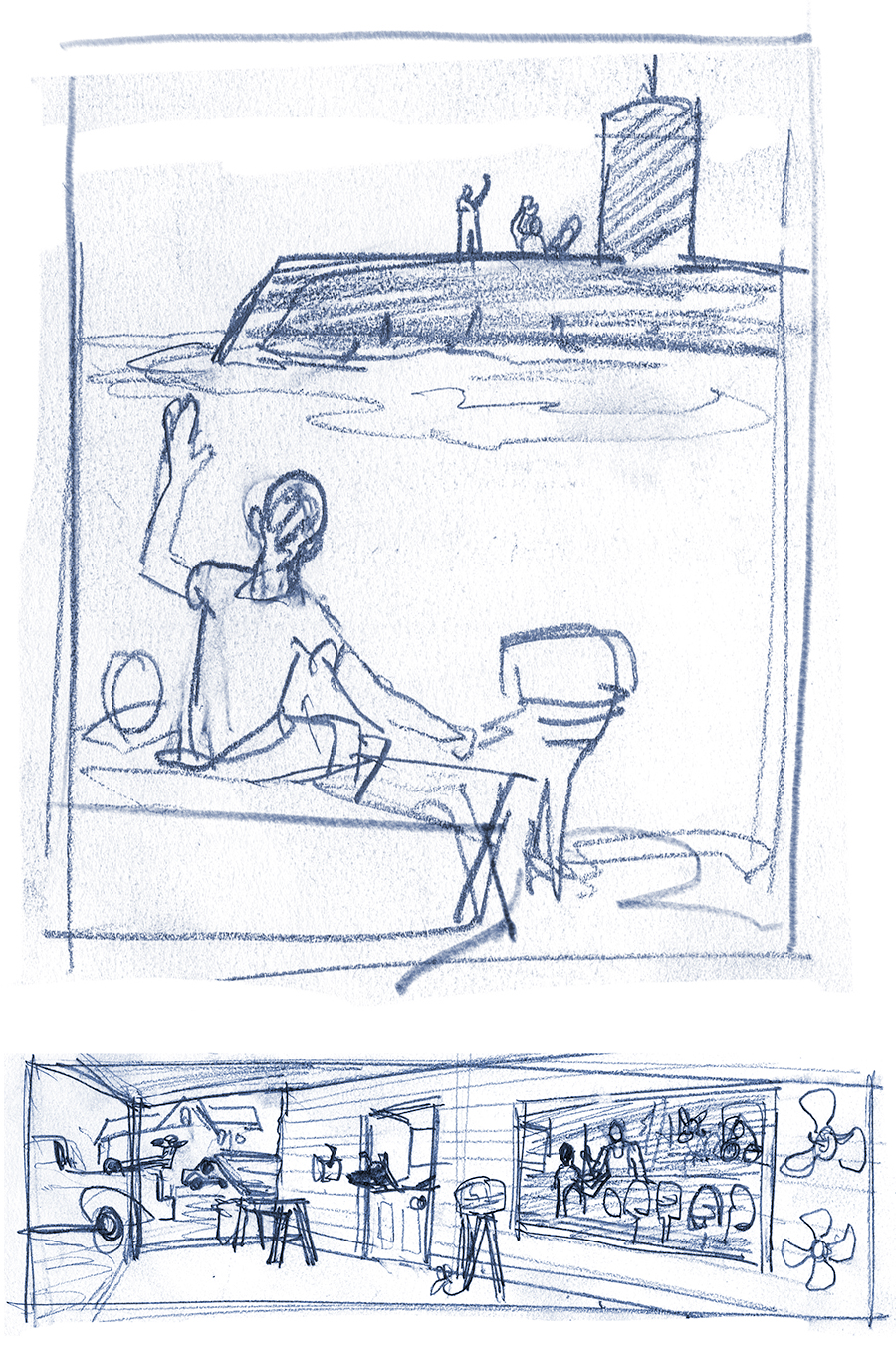

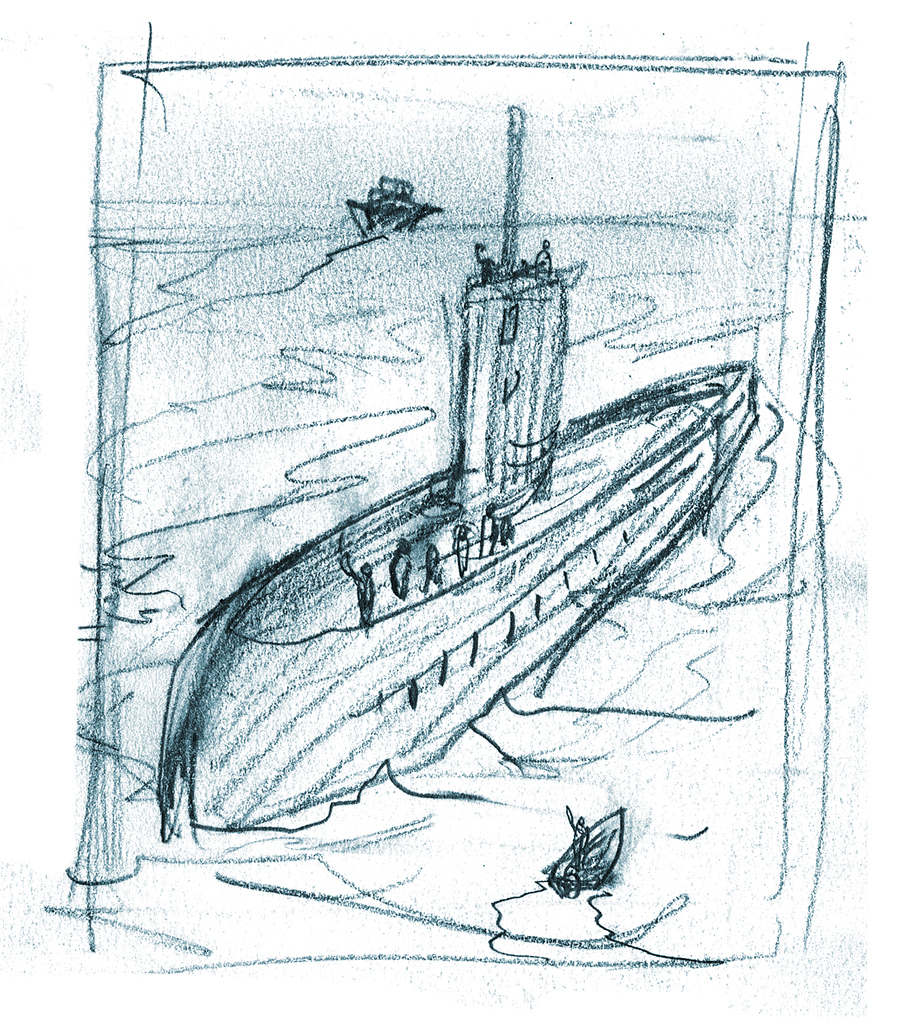

The next day, it was time to run through the Cape May Canal into the bottom of Delaware Bay. We were getting beaten up pretty badly, my little boat and I, though I wasn’t as concerned about myself as I was about my boat. It wouldn’t be able to take much more pounding. I had planned to run right up the middle of Delaware Bay, to the Chesapeake & Delaware (C&D) Canal, but it was too rough, so I started up the middle, and decided to get to the western side of the bay as fast as I could. I wanted to run up closer to the Maryland shoreline and hide from the wind and waves. I was making pretty slow time against the nasty conditions when I heard a voice. “Are you okay, son?” It took a few minutes to realize the voice wasn’t coming from the Almighty, but from a submarine off my starboard side.

I said I was alright, and they surfaced, talked to me for a while, and went on their way. It was a nice feeling to have somebody—anybody—notice my current circumstance and offer assistance. That was just the first of many interactions with strangers who were genuinely concerned about my welfare (read: stupidity), offering help when I needed it most.

I finally made it to the C&D Canal late in the afternoon. I was running along its edge when I hit a large rock that broke apart my gear case. I wasn’t far from a small beach under the St. Georges Bridge in Delaware, so I pulled my boat up onto the sand and tried to figure out where I was and where I might find spare parts.

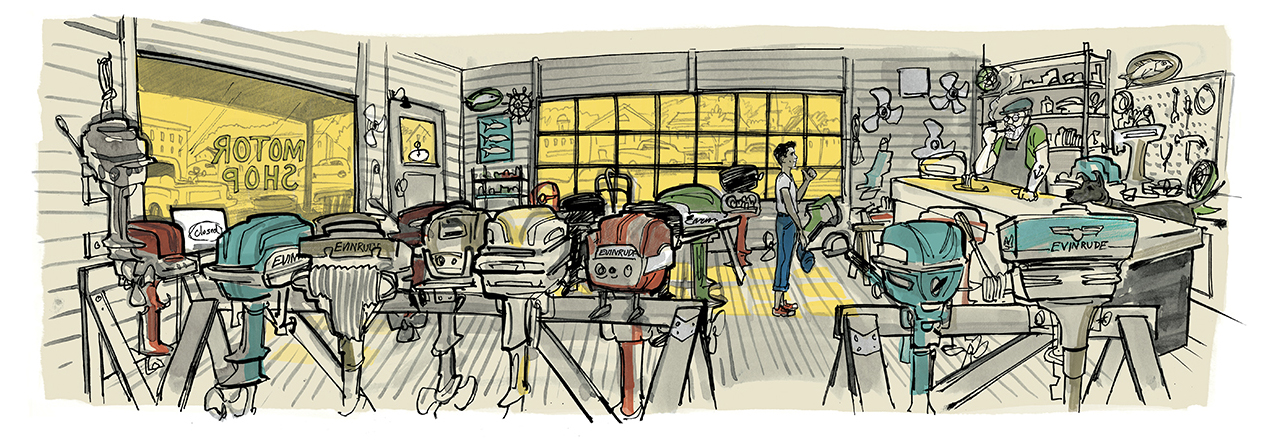

It was late in the day, but I had to take the lower unit apart to assess the damage. I split the case open and found lots of metal debris that had once been the pinion that drove the gears. The clutch dog was also fractured and needed replacing. I learned from someone at the beach that the nearest Evinrude dealer was in Wilmington, Delaware. It may as well have been in Alaska. I climbed up to the main highway to start hitchhiking. In three rides I got close to where I needed to be and found the little dealer downtown.

There are three gears in an outboard motor: the pinion, forward and reverse. I only needed the pinion, since the other two were scarred up but not too badly damaged. I didn’t have much money, and the dealer told me the gears only came in an expensive “matched set.” I convinced him it really didn’t matter if he broke up a set, and after much haggling he sold me the pinion I needed without the other two parts.

With my new gear, new clutch dog and two tubes of gear oil in hand, I started back to my boat. Since this side trip had taken up most of the day, I settled in for another long night of mosquitoes. The next morning, one of the families that had been on the beach when I first landed had come back with cookies and a sandwich for me. I was much thinner then, and probably looked like I couldn’t miss another meal.

I got most of the gear case together that night and finished working on it early the next morning. I was able to leave a few hours later, setting off through the C&D Canal into the Chesapeake Bay, which I had been told was a “nasty” body of water.

I reached Annapolis that night and tied up at the end of the municipal dock. I walked down the dock to the street, noticing a 40-foot boat that had come from Freeport, the same town on Long Island I had left from. I introduced myself to the owners, and it turned out I knew their son. The father walked with me to the end of the pier to check on my boat and about lost it when he saw how small it was. They were really nice people. They had me tie my boat up behind theirs and come aboard for dinner. After a great meal (my first in some days), I got to sleep in a bunk on their boat, which was heaven.

I was just a few miles from crossing the mouth of the Potomac River. I thought I was doing well and making good time until my engine started making a loud knocking sound; I knew something was wrong. The land to my right didn’t look too heavily inhabited, with two or three homes along the shore. I beached the boat about a mile past them. There happened to be a picnic table nearby, so I settled in to sleep on top of it (this time with a lot more mosquitoes and other critters).

The next morning, I was still sitting there on the picnic table trying to better understand where I was and how I was going to get help. I had disassembled the outboard all the way down to the last nut and bolt. I couldn’t see anything wrong with it, but I was sure that the knocking noise was coming from the internal bearings. In those days, you really didn’t need much in the way of tools to work on motors—two or three wrenches, a pair of pliers and a screwdriver could do the trick. I got it apart and thought I had figured out what I needed to buy when I heard a noise. I turned around to find a big barking dog running up on me. Behind the dog was an older gentleman walking down the beach. He asked what I was doing there and I told him about my experience so far. He had me walk with him back to one of the houses I’d seen the day before and offered to let me stay with his family.

Since the family had only one vehicle—which the father used to get to work each day—I started hitchhiking to the next town over. I was told there was an Evinrude dealer there and he might have what I needed. When I arrived, though, I discovered he didn’t have the parts I wanted, so I placed an order for them. Back in those days, there was no FedEx, so I was stuck waiting a week for the parts to come. Even so, I hitched up that road a number of times to see if they had come in. It was real hot and the road was under construction and dusty. A shower outside under the hose always felt good when I got back from each trip.

When the parts finally came, I hitched into town to get them. I put the engine together, said my goodbyes to the family, pushed the boat out and started the motor. But after running for a minute, the noise came back. I headed back to the beach, where I learned a valuable lesson in diagnostics.

I took the engine apart, only to find nothing wrong. I realized then I needed more help. The dealership where I’d purchased the parts was closed, but there was another outboard dealer not too far away. I put the engine in the back of the father’s truck. At 4 a.m., I was up from my chair on the porch where I had spent the night, waiting to go with him. At 5:30 he dropped me and the engine off on the dealer’s doorstep. I sat there guarding my precious motor until the owner arrived at 8:00 a.m. I told him my story and he said he’d see what he could do. I hung around all day, sweeping the floors and doing whatever else needed to be done around the shop.

My ride was coming back at 5 p.m., so I got a little worried around 3:30 when they still hadn’t checked out the motor. Eventually they put it in the test tank and started it. The knocking noise was still there; it sounded bad. The mechanic seemed to have diagnosed the problem. Having rummaged around for an old flywheel, he put it in the motor. Problem solved. I asked what I owed him and he said he would check with his brother and bring me the bill. I was pretty scared since I didn’t have much money left after buying all of the unnecessary parts. After a while he came out with a business card that was folded in half. I hesitantly opened it and saw what he had written: Paid in Full. GOOD LUCK ... Bob and Jim.

The next day I finally left for real, heading toward Norfolk, Virginia. I didn’t have to go far to find more trouble. The mouth of the Potomac River was very rough—the largest waves I’d ever seen. I got pretty good at powering up a wave and coasting down the back side to keep from stuffing my small boat into the trough. That is, until I got a little antsy, ran too fast down one and stuffed the whole boat into the next one. The boat was suddenly filled to the top with water, but somehow the motor was still running. I opened it up to try and drain it but instead the motor stopped running altogether. There’s an old saying that the best bilge pump is a scared sailor with a bucket. I didn’t have a bucket, but I practically melted a little plastic hand pump I had. The motor had quit because the tied-in tanks had turned over in the water and there was no fuel in the engine. Oh, and I didn’t notice that all my “worldly belongings” had washed away.

I finally got the water level in the boat down to where I was floating a little more confidently and no more water was coming over the sides. I turned the gas tanks over, tightened them down and got the engine started.

Norfolk Harbor was a great sight. There were lots of boats and ships moving around; there was even an aircraft carrier anchored in the middle of the harbor. I went right up to it and touched the side. (I don’t recommend trying that today!) Not knowing where to go, I looked for somewhere to tie up. I found an abandoned dock and tied to it.

The beginning of the Intracoastal Waterway, from Norfolk to Key West was not the same back then. Nowadays, you have a great start to the waterway, with one lock and lots of other boat traffic. In the ’50s, the only choice I seemed to have was the Dismal Swamp Canal (not ideal for a 16-year-old alone). This interesting start to my experience with the ICW was about 21 miles of almost straight waterway with trees lining the sides and two locks to get through. Having never been through a lock, I looked forward to that new experience.

I came up to the first lock and, not having a horn or a radio, sat there yelling and whistling for someone to open it. I finally beached the boat, walked up to the lockmaster’s office and told him I was southbound and asked what I needed to do to get it open. He said my boat was too small to open the lock just for me. I noticed a small cradle on wheels and a pair of train rails that ran up and over the lock area, so I asked if I could use that to get around the lock. He said yes. I lowered the cradle into the water and got my boat sort of onto it. The two of us pushed and pulled to get the little rail car plus my boat up and over the lock.

The lockmaster told me there was another lock a few miles farther down, but that one didn’t have a rail car. I figured I’d worry about that when the time came. I roared up to the next lock at 30 knots and miraculously it started to open. I pulled in and told the lockmaster I thought I would have trouble getting through. “The guy at the other lock called and said there was some crazy kid on his way to Florida, and I’d better let him through,” he said.

I’d been lucky with weather, until I wasn’t. Just outside of Morehead City, North Carolina, I ran into the worst storm I’d ever experienced. The thunder and lightning weren’t the biggest concern: It was raining so hard, I couldn’t see anything at all. I couldn’t even see the chart to guess which way to go. I was creeping along and passed a channel marker pole. I turned around, put my bow up against the pole, kept the engine in gear and sat there running like I was trying to push the marker over.

When the rain let up a bit, I read the number off the marker and found my location on the chart. The channel wound around quite a bit, and if I hadn’t stopped and held my position against the marker, I would have surely run into the marsh and really been stuck. After an hour, the storm let up enough for me to move slowly to the next marker—and so on. I found my way to a commercial dock at Morehead City and convinced a guy to let me tie up my little boat there, in the storm, without a fee.

I walked into town, thoroughly soaked, to find a place to stay that wouldn’t clean me out entirely. This would be the first motel I’d ever stayed in: a real treat. I just needed a little more shelter than my picnic tables provided. I went to the first place I came across, a motel made up of small, single-room cabins with a “Heat” sign out front. I recall the cost being around $15, which seemed like a lot for someone who just wanted a dry place to sleep. I took a bath, (there wasn’t a shower head) and felt a lot warmer and drier and quickly fell fast asleep in a real bed.

On this trip, I passed by all the great vacation spots I would hear about later in life, including the Outer Banks. I passed through at 30 knots, without stopping, except for gas when I needed to refuel. I had six, 6-gallon tanks tied up inside the boat so I could limit stops for fuel.

I ate up the miles pretty quickly in North Carolina and was feeling good about things. When I crossed into South Carolina my engine exhaust was steaming a little more than normal. I passed under some bridges that, I later learned, led to Myrtle Beach and kept going toward a pretty desolate part of the Eastern shoreline. The outboard was getting really hot. If I didn’t stop soon I would do some major damage to the engine’s new parts. But there was no civilization I could see, no roads or signs of life anywhere.

I tied the boat to a tree and, using my trusty pocket knife, cut my way through the heavy brush and swamp along the waterway. I finally got to the small drawbridge I had passed a couple of miles earlier. It had taken me some time to get there. Scratched, cut and eaten alive by mosquitoes, I must have looked feral. Walking into the bridge tender’s little house, I asked him where I was and if the nearest town had an outboard dealer. I learned the nearest town was Myrtle Beach, and a few miles west of there was a dealer.

The problem was, I needed to get the boat back to the bridge without running it and doing further damage. So, I went to the middle of the bridge, stood up on the rail—about 30 feet above the water—and dove off. I can’t imagine what the bridge tender thought. I swam and floated downstream to my boat. The growth along the shore was so dense that I couldn’t walk along the water’s edge and pull the boat, so I started swimming with a line tied around my waist like a human towboat. After an hour, during which I made surprisingly little headway, a fisherman came along and wondered what the hell I was doing. I told him I was trying to get back to the bridge. He felt so sorry for me, he told me to get back into my boat and threw me a line. It didn’t take too long to get back to the bridge under power. The fisherman dropped me off at an old, abandoned boathouse, just a stone’s toss from the bridge.

After sleeping on a plank alongside my boat, I walked and hitched into Myrtle Beach the next morning. I found the dealer and waited for him to open up. I figured I needed a water pump, a simple fix, but I was told I would have to order the parts. The cost of those parts would exhaust what little money I had left, but I ordered them, and walked into the busy beachfront area to see if I could figure out some way to earn money. My mother had sent me money when I’d run out the first time, but I didn’t want to go back to her for more. (She was a single mom raising my two younger sisters.)

I got lucky as a fry chef at a small grill. The owner didn’t want to work that hard and said I could work from 3 to 11 p.m. each night. I started work immediately. He showed me how to dump big bags of potatoes into a machine that cut them up into french fries, fry them and bag them for sale. This was before McDonald’s, and man, I’ll tell you what—those fries were really good. I was quite skinny then, but boy, did I live on those things for much of the time I was stuck in Myrtle Beach.

The dealer wouldn’t order my parts separately, so I had to wait until he needed enough parts for a bulk order. I went every day to ask if they had come in. I’m sure he got tired of me pestering him. By this time I had enough money to pay for them. I also had my fill of fries and I wanted to get back on my way. School in Miami would start in a week.

The parts finally came in and I pulled the lower unit off to change the pump. That night I said goodbye to my fry “boss” who was not happy to have to come back to work himself.

My run down the coast of Florida was a long sightseeing trip with a few gas stops thrown in. Navigating the narrow ICW was certainly easier than many of the larger bodies of water I’d come through, and I made good time. Since my little boat made little to no wake when running fast, I blew through some of the slow no-wake zones. It was more difficult to find places to sleep along the Florida waterways, since so much of the shoreline was filled with fancy homes. I made use of a couple of small islands with sand beaches that today are weekend “sandbars” for partiers.

My last fuel stop was in West Palm Beach, and I thought it was farther to Miami than it turned out to be. I finished the trip with a few full tanks in tow, and wished that I had the money instead. My final destination wasn’t, in fact, Miami, but actually a little south of the city at Dinner Key. I called my boss at Snapper Creek Marine and told him when I’d arrive. I didn’t own a trailer, but they were going to swap a boat out to come and pick me up.

When my boss arrived there was no celebration, just a walk in the shallow water to get the boat on the trailer and tied down. We took it to the shop and I loaded it onto some cement blocks in the yard. I worked the rest of the day to earn some money.

Unfortunately, that was the last time my little boat ever saw the water. I sold the motor for much-needed spending money. The marina changed hands a number of times, but my boat remained, rotting away on those blocks. After graduation I went north to work and attend school and never saw my boat again.

I learned so many life lessons on that trip. The experience helped me in my career and in other competitive undertakings, and I wouldn’t trade it for anything. Today, no parent in their right mind would allow their teenager to take on anything close to this type of endeavor. I have three sons of my own who have cruised extensively, but there’s no way I would let them recreate the journey I enjoyed at 16. Things are just different today, I’m afraid. But the truth is, my adventure taught me how to deal with many types of situations and people. I also learned at an early age that there is great joy in getting out into the world on a boat. Everything looks quite different from the water.